A new climate change plan in the European Union, which has been lauded for its ambitious targets and aggressive action on emissions, will sacrifice carbon-storing trees, threaten biodiversity and outsource deforestation, according to a new paper.

The paper, published this week in Nature, calls into question the plan’s treatment of biomass — organic material from trees, plants and animals — as carbon neutral, as this incentivizes cutting down trees and planting more crops that can be burned for energy. Burning biomass not only removes trees that can store carbon, but releases greenhouse gasses as well.

The authors warn this will destroy habitats for important wildlife and spur deforestation, and that Europe does not have the land space to produce additional biomass. Europe already relies heavily on land abroad for farm production and these imports account annually for about 400 million tons of carbon dioxide — eclipsing the benefits from the growth of European forests in recent decades.

“Thus, rather than Europe having spare land or wood to supply additional bioenergy or other consumption, climate strategies require the bloc to ‘give back‘ land and carbon either to nature or to supply others,” the authors wrote.

There is a more sustainable path forward for Europe, the authors point out, but the current climate plan as written diverts 20% of Europe’s land for crops to those that can be burned for energy.

What is Fit for 55?

The plan in question is called Fit for 55 — a law that mandates the EU reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (relative to 1990 levels). It also aims to make the entire EU climate neutral by 2050. The package includes a number of plans to achieve these goals including bolstered energy efficiency, an emissions trading system, more infrastructure for renewable energy, stricter emissions standards for vehicles and other measures.

The plan is the first of its kind on the planet. The European Parliament and the European Council are still negotiating the final details.

Why is biomass a problem?

The new Nature analysis says not only must the world decrease fossil fuel consumption but also its “land carbon footprint” — which is “the quantity of carbon lost from native habitats to supply agricultural products and wood.”

“By treating biomass as ‘carbon neutral‘, [Fit for 55] create[s] incentives to harvest wood and to divert cropland to energy crops, regardless of the consequences for land-based carbon storage.”

Growing trees and crops strictly for energy use has urgent food security consequences as well. The authors estimate that cutting 85% of Europe’s biodiesel use and half of U.S. and European grain ethanol would “free up enough crops to replace all Ukraine’s vegetable oil and grain exports.”

Additionally, Europe’s reliance on food imports means its forests have grown, but the region’s imports led to about 11 million hectares of deforestation elsewhere, mostly in the tropics.

This deforestation destroys habitats for wildlife, and means carbon stored in trees can release back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

Biomass accounting error

The plan considers biomass carbon neutral because the emissions from burning it would be presumably offset by growing new plants. The new paper argues this is faulty logic because land is required to grow those plants. Using land for biomass crops means you cannot grow food on the land, so other land needs to be converted or the food must be imported. Also, trees cut down for biomass means less carbon stored in the forests.

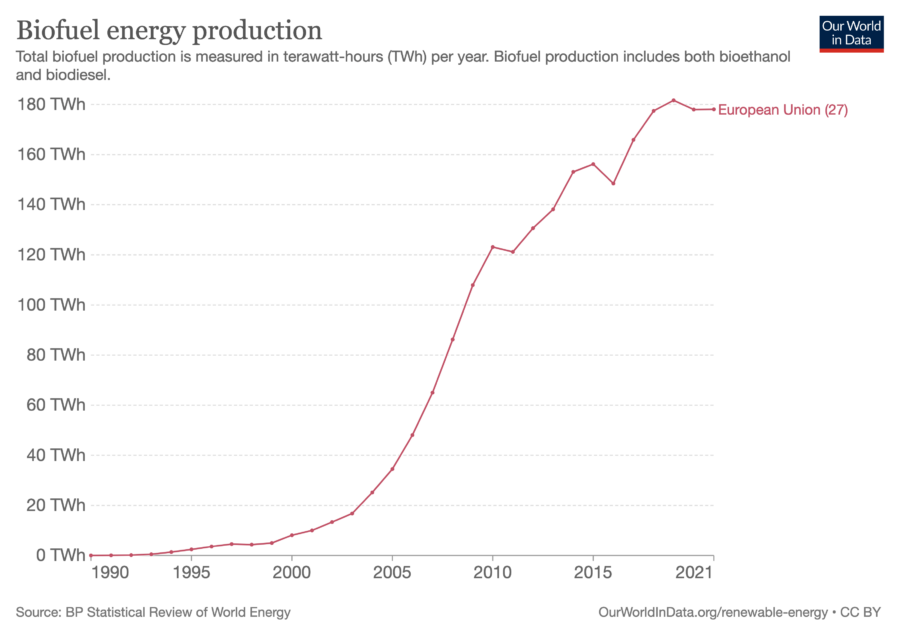

The Fit for 55 estimates biomass use will double from 2015 to 2050 — requiring annual biomass amounts that are double Europe’s current wood harvest.

“Land is not ‘free’” the authors wrote.

How can Europe’s plan improve?

The authors estimate Europe could free up roughly 17 million hectares of land by 2050, by reducing both consumption of biomass fuels and livestock farming. This would free up land to grow more of its own food and reduce imports.

The authors also recommend restoring habitats, drained peatlands and preserving older forests.

“Europe could reasonably choose a mix of these goals for its land future, but they all require a smaller footprint.”

See the full paper in Nature.